Structuring Cycling Training Using ‘Block Periodisation’

The concept of periodisation refers to the manipulation and sequencing of selected training variables (e.g., load, volume, intensity, exercise type) within the framework of specific cycles throughout the year to optimise athletic performance for major competitions (Garc ́ıa-Pallare ́s et al. 2010).

Periodisation in a general sense is a widely used term within coaching circles, and has roots dating back to the work in the 1960s of Soviet sports scientists in the former USSR.

More recently though, coaches have looked to overcome certain limitations of traditional approaches to periodisation using more novel methods, one of which is “block periodisation” (also known as “block overload”), which we’ll examine in this piece…

Block periodisation

‘Block periodisation’ or ‘block overload’ involves front-loading a series of challenging workouts in the first microcycle of the mesocycle*. These challenging workouts focus on a specific ability area, such as developing VO2max/aerobic capacity or lactate clearance. This has the goal of stimulating larger adaptations in this specific ability area than would usually be possible using a more traditional method.

This goal is achieved by inducing a large stress or adaptive stimulus via a concentrated load, which then facilitates a strong signal for adaptation or improvement in this specific ability.

After this overloaded microcycle, there is typically a vast reduction in amount of these challenging ability-specific workouts in the following microcycles. High intensity training volume is reduced to provide the necessary space for recovery for adaptation, and to allow an opportunity for higher-volume, low intensity sessions to be included to help maintain base aerobic fitness. The improvements made through the first microcycle are maintained throughout the rest of the mesocycle with the inclusion of a much smaller number of high-intensity workouts.

Traditional periodisation

This block periodisation approach is distinct from the more common and traditional periodisation approach, where the number of weekly high intensity workouts are constant in each.

The goal in using the block periodisation approach is that by focusing on overloading one specific ability, the athlete should theoretically be able to achieve a greater improvement due to a heightened or stronger targeted stimulus, which can then be maintained throughout the remaining microcycles of a mesocycle and then carried forward into the next.

Block vs Traditional

Below is a visual representation of these two periodisation approaches.

Let’s say we have a coach who wants to improve the VO2max of an athlete (their ‘aerobic capacity’ or maximal oxygen uptake level) by manipulating the workout sequencing of the training plan.

Using a traditional periodisation approach over a 4-week long mesocycle, the program might resemble the following:

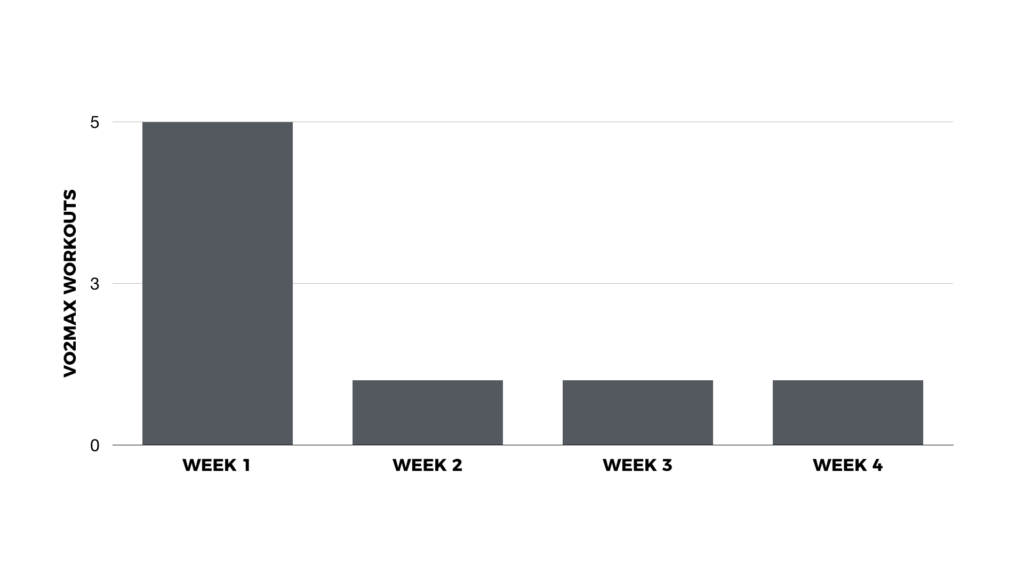

As you can see, each microcycle or training week consists of two VO2max workouts and this doesn’t change from week-to-week. If the coach instead opted to use a block periodisation approach, the organisation of these workouts and intensities would look more like this:

In this example, you can see that the first week in the mesocycle is front-loaded with 5 VO2max workouts. This frequency is then reduced to just 1 high intensity workout for the following 3 weeks of the mesocycle in order to maintain this specific fitness and provide a lower volume of high intensity that’s ideal for a supercompensatory response.

What’s important to note here is that in both examples, the same total VO2max workload is performed, but is distributed very differently over the 4-week mesocycle. The athlete’s training in the first week would almost entirely be composed of VO2Max sessions, whereas the following 3 weeks feature just 1 VO2Max workout.

Furthermore, it’s likely that the additional workouts in the following weeks after the overload would mostly be made up of lower intensity workouts to facilitate recovery and subsequent adaptation, as well as to maintain or develop other important components of fitness (i.e. peripheral aerobic adaptations like improvements in mitochondrial content/quantity, which come largely as a result of lower intensity, higher volume training featuring a high number of muscle contractions).

Benefits

So what are some of the ways that using a block periodisation approach could potentially improve the adaptive response?

Streamlined

One of the main problems when an athlete and coach are trying to develop many different fitness components at any one time is the conflicting training responses that can occur. It may be that a coach is unwittingly trying to improve the athlete’s fractional utilisation (i.e. % of the VO2max at which the threshold power sits) but also seeking to develop their sprint ability and glycolytic capacity at the same time. In this example, these two objectives require very different aspects of fitness to be trained, and in some respects these training objectives are in conflict (e.g. improving glycolytic power can drive down fractional utilisation).

Block periodisation allows different abilities to be worked on separately, and at the time times in the training cycle.

Peaking

Block periodisation can sometimes help athletes to achieve multiple peak-performances throughout the course of a season or macrocycle, by including concentrated blocks of ability-specific training between races. These blocks can focus on achieving improvements in race-critical abilities, and these improvements can be stimulated far more quickly by blocking together intensive sessions. This means fitness can potentially be adjusted accordingly in a more nimble way, which is especially important if the nature of the competitions at different periods in the season differ (for example, a MTB athlete who is looking to race some XCO or short-track events, but then wanting to mix in some longer marathon (XCM) races too).

Simplicity

Block periodisation can help simplify the short-term training objectives. On the side of the athlete, there’s clarity in what response the training is trying to elicit, which may foster more buy-in and motivation from them. When training elements can be simplified without compromising its effectiveness, it’s generally a positive step to take.

Maintenance

Adaptations facilitated by an overload block can be maintained with a reduced focus on this specific ability. This allows time for the athlete or coach to focus on developing other aspects of fitness without having to worry about certain abilities decaying.

Indeed, block periodisation is also closely tied with the concept of ‘training residuals’ – which is that different fitness components have different periods of training and detraining. For example, aerobic adaptations (such as mitochondrial and capillary density, and cardiac output) are thought to take the longest time to develop, but also detrain at the slowest rate (~months) (Issurin, 2008). In contrast, abilities like increased glycolytic rate and neural activation of fast-twitch fibres, appear to respond more rapidly, but also detrain much more quickly (~weeks and ~days respectively) (Issurin, 2008). Therefore, by structuring smaller blocks of training, this allows for switching between different aspects of fitness at appropriate frequencies to see development or maintenance of these abilities.

Drawbacks

What might be some of the shortcomings of block periodisation compared to using a more traditional approach to training organisation?

Non-functional overreaching

The first is that block periodisation may overtrain some cyclists. Particularly vulnerable are those with lower fitness levels and training history. The concentrated weeks at the start of a mesocycle can be both mentally and physically challenging and a string of 5-6 hard workouts in a row may be too much for some cyclists to handle. If athletes and coaches use this periodisation approach before a major event and push the load too high, this could easily ruin a big part of the season.

Practicality

Block periodisation isn’t always practical model for all athletes. Bad weather and other factors can make it very difficult for those with rigid schedules or a lack of training time to perform such a concentrated string of workouts. In contrast, a more traditional flat periodisation approach might allow you to shift sessions around as needed over the course of a mesocycle and this may result in greater improvements.

One-dimensional

Traditional periodisation can allow for multiple fitness components to be focused on at a given time. Whilst we’ve discussed this previously as a limitation, if the athlete and coach understand the interactions between different training responses and can carefully combine compatible focuses together effectively, this may result in a larger net gain in overall performance compared to a short-term focus on just one.

Considerations

Here are some final pieces of advice when it comes to maximising a block periodisation approach.

Firstly, as with most novel approaches to training manipulation, athletes and coaches need to assess their individual circumstances and decide whether a particular approach has the potential to work and be compatible with their unique schedule, goals, abilities, training history etc.

We’d also recommend cautiously experimenting with different periodisation approaches at non-critical times of the season (e.g. during the approach to lower priority competitions, or when higher priority competitions are many weeks away).

It’s important to note that any approach that promises to offer the opportunity for rapid and large improvements will always be accompanied with a comparatively large risk. These ratios should always be weighed up and approached sensibly and conservatively, and will be different for each athlete.

*It’s worth noting that the term ‘block periodisation’ has also been used in a more general context, where the basic principle is that training is structured in relatively short blocks, with each focussing on a very specific fitness component (such as developing VO2max, or building anaerobic capacity). Importantly, the focus of these blocks can be tailored to address the athlete’s specific ‘gaps’ (i.e. race/goal-specific performance limiters). However, this conceptualisation of ‘block periodisation’ does not require that intensive sessions are front-loaded within a mesocycle. Instead, intensity can be distributed in any way that suits the athlete.

Free Workout Handbook

Be sure to grab our Key Workouts Guide, a short and practical PDF download that outlines 10 effective training sessions to develop the major components of high cycling performance:

References

Bakken, T. A. (2013). Effects of block periodization training versus traditional periodization training in trained cross country skiers.

García-Pallarés, J., García-Fernández, M., Sánchez-Medina, L., & Izquierdo, M. (2010). Performance changes in world-class kayakers following two different training periodization models. European journal of applied physiology, 110(1), 99-107.

Goutianos, G. (2016). Block periodization training of endurance athletes: a theoretical approach based on molecular biology. Cellular and Molecular Exercise Physiology, 4(2), e9.

Issurin, V. (2008). Block periodization versus traditional training theory: a review. Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 48(1), 65.

Issurin, V. B. (2010). New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization. Sports medicine, 40(3), 189-206.

Rønnestad, B. R., Hansen, J., & Ellefsen, S. (2014). Block periodization of high‐intensity aerobic intervals provides superior training effects in trained cyclists. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 24(1), 34-42.